Digital Infrastructure for the Post-Pandemic World

The emergence of COVID-19 forced a shift away from workplaces and schools to online working and learning, but this digital transformation, has not been evenly experienced by all Canadians. Many workers and students have confronted barriers of a structural and/or discriminatory nature that have blocked them from taking full advantage of the opportunities to work and learn online.

Identifying and addressing the barriers to accessing essential digital infrastructure is key to addressing unequal access to skills training, education and employment opportunities. This report examines the key components of Canada’s essential digital infrastructure system, highlights worrying inequalities that exist within this system, and offers recommendations on how to quickly reduce some of the most glaring obstacles that prevent many of those who would benefit the most from accessing training, education and employment opportunities digitally from doing so.

Key Takeaways

Executive Summary

If Canadians thought the country was speeding towards a digital economy before the pandemic, they couldn’t help but feel it had arrived — virtually overnight — after the virus touched down in Canada.

Indeed, the need for Canadians to work and study from home to “flatten the curve” has become the foundation for much business activity today. When lockdowns hit in March 2020, many working lives, not to mention social lives, went from in-person to online. A total of 4.7 million Canadians who do not normally do so started working from home. As of December 2020, nearly a third of Canada’s workforce was still working from home, including 2.8 million people who would not normally do so.

Ironically, while digital business and education theoretically could ensure better access to both for a large number of Canadians, restricted internet access will block this for many. In short, digital transformation has been experienced unevenly and, at least so far,has served to deepen some inequalities rather than ease them.

Access to a computing device and a reliable internet connection is essential according to Canada’s broadcasting and telecommunications regulator, which named broadband internet a “basic service.” And yet, it’s not a service accessible to everyone. Geography and affordability both play roles in limiting access for many. There are still locations in Canada where internet service is inaccessible or impractical. Either the quality is non-existent or unacceptable or the cost is prohibitive — sometimes it’s both. Residents of Nunavut, for example, pay six times more for broadband service than the average Canadian. Internet providers respond to market demand and, in these sparsely populated regions, it’s clear government action is necessary to make good on the CRTC’s assertion of access as a right. Affordability remains another challenge for some urban and rural households alike.

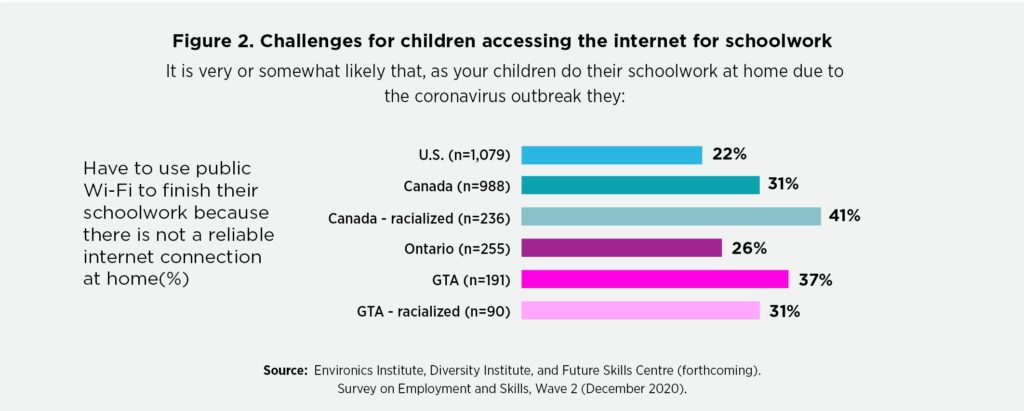

Internet inaccessibility often hits already marginalized communities in ways that compound already existing discrimination. The CRTC found that in 2020, just 34.8 percent of First Nations reserves and 45.6 percent of rural households have reliable and affordable internet access, while 98.6 percent of urban households do. Access among those who speak neither French or English — often new Canadians —slips to 90.6 percent. This is related to the number of racialized households in the Greater Toronto Area that are finding at-home schooling challenging. More than 25 percent of such households said their children were not able to complete their homework because they didn’t have access to a computer at home.

A federal government “connectivity strategy” from 2019 set the goal of providing good connectivity to 98 percent of Canadians by2026, and 100 percent by 2030. Meanwhile, programs such as Rogers’ Connected for Success, TELUS’ Internet for Good and the federal government’s Connecting Families exist, but don’t offer the basic standard speeds of connectivity. And in well-serviced households with multiple users — school-aged children and parents who are working from home, for example — even this standard is proving to be inadequate.

Compounding the barriers of geography and income are such factors as time and access. Those who can’t afford internet service are relying on public access, much of which — coffee shops and municipal buildings, for example — has been shuttered during the pandemic. Places such as libraries require travel time from users and such places are operating at reduced capacity. Households stuck sharing computing resources may find similar conflicts.