Could engaging mature adults in skills training be the key to addressing Canada’s labour shortage?

Canada is facing an unprecedented shortage of skilled workers. According to data from Statistics Canada, the unemployment to job vacancy ratio was at a record low during the third quarter of 2022: for each job vacancy, there were 1.1 unemployed people.This ratio has been on a steady decline since 2016, indicating that employers are having difficulty filling positions. This labour shortage is seen across provinces and sectors, including manufacturing, health care and social assistance, construction, retail trade, and accommodation and food services.

Some have pointed to what has been called the “Great Resignation” as the cause of this shortage: the wave of retirement that is sweeping across Canada. More Canadians retired from their jobs in 2022 than in the previous two years. Moreover, the workforce is made up of a record number of mature adults aged 55 to 64 years who are nearing retirement.

How can Canada’s labour shortage be addressed? While an aging population has been suggested as one cause of the shortage, it has also been proposed as a solution. The idea is that mature workers be retained or, for those who have retired, brought back into the workforce. A recent report from Scotiabank referred to mature adults as “overlooked and underutilized.” Tapping into this group, therefore, could help to address the shortage.

One way to retain and attract mature adults back into the workforce might be to engage them in skills training, either to add to their skill set or to learn new skills. To design a skills training strategy tailored for mature adults, however, it is important to understand if this group is already involved in skills training and, if so, to what extent.

Using data from the Survey on Employment and Skills, we looked at who reported having completed training since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and how factors associated with training varied for older and younger workers. The survey, conducted by the Environics Institute for Survey Research in collaboration with the Diversity Institute and the Future Skills Centre, explored the employment experiences of Canadians relating to education, skills and employment. It looked at perceptions of job security, the impact of technological change and the value of different forms of training.

The COVID-19 pandemic period is unique in recent history in how it has affected work and people’s ability to train; it has created time for many workers, but it has also limited training options owing to public health mandates and best practices. We used data from the 6,604 respondents who responded to the fourth wave of the survey, conducted March to April 2022.

Mature adults trained less than younger adults; importance of digital skills highlighted

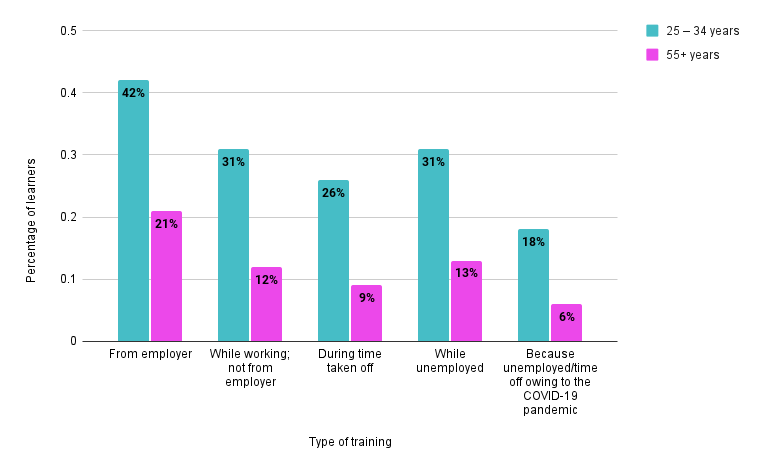

Figure 1. Respondents that reported engaging in training since the COVID-19 pandemic: millennials vs. mature adults

Across all types of training, mature adults engaged in less training than did younger adults (Figure 1). Of the mature adults that engaged in training, 17% took courses related to digital skills, such as information technology, computer, technical or graphic design skills. These results are consistent with other results from this survey, as well as data on the future of the workforce that highlights the increasing demand for digital skills. Often, the perception is that digital skills refer to deep technical skills such as coding languages; however, there is a high demand for basic digital skills, such as word processing.

For mature adults who did not engage in training, over 56% said this was because they already had the necessary skills, compared to 48% of millennials. These results suggest that most mature adults are not engaging in additional skills training, nor do they seem to have interest in doing so. This may be because they are more confident in their abilities when faced with new challenges compared to millennials (71% of mature adults vs. 58% of millennials). Or, it may be because they see their careers coming to an end, whereas younger adults are planning for their future. Perhaps mature adults feel that additional training is not needed due to their level of experience.

Another possibility, however, is the climate of the workplace, where many older adults may feel under-valued, marginalized and discriminated against. Among mature adults looking for a job, 59% believe their age is the reason they can’t find a job; this is consistent with previous research showing that mature adults frequently experience ageism in the workforce. Other data shows that while mature workers are perceived as warm, they are also stereotyped as lacking adaptability and being resistant to change, which may lead employers to avoid investing in additional training for this age group. These stereotypes may be the reason why mature adults are not engaging in training: they may not feel like their employer would see the value in them participating in additional skills training and thus may avoid it.

Implications, conclusions and future directions

If engaging mature adults in skills training is important to addressing the labour shortage in Canada, then efforts might be needed to change mature adults’ perspective on their importance in the workforce, and to highlight the value of skills training. Further, initiatives may be needed to combat the stereotypes that may be a barrier to mature adults undergoing training.

Overall, these results shed light on skills training engagement in mature adults and highlight some important issues for the skills training ecosystem to grapple with when developing programs to support skills training for mature adults.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint, official policy or position of the Future Skills Centre or any of its staff members or consortium partners.