What we’re talking about when we talk about the future of skills

The world of skills development is changing swiftly, for three reasons: 1) population aging is leading to widespread labour shortages, which highlights a nation’s relative policy reliance on skills development of its own people versus immigration as the primary response; 2) the location of skills development is shifting, from costly and time-consuming certification through colleges and universities to shorter-term and on-the-job training; and 3) the role of technology historically both augments and replaces labour, but the latest set of digital technologies is impacting the highest-skilled, highest-paid jobs in an as-yet unpredictable way.

What skills do we need most amid widespread labour shortages?

In nations throughout the global North, more people are exiting the labour market than entering it due to demographic trends (retiring baby boomers and decades of falling birth rates). The Canadian economy will need more people from abroad to avoid stagnant or even falling standards of living; and that will be true elsewhere. We will be competing with many other countries in the global north to attract workers from the global south, in every skill category.

Canada stands out internationally with its growth in immigration occurring in tandem with our appreciation for what immigrants bring. For decades, immigration policy focused on landing “the best and the brightest” – immigrants with the highest skills and investment capital. For decades, skill shortfalls were only an issue for particular regions and sectors, but future shortfalls will be for all types of skills, everywhere. From both a labour market and a business point of view, bargaining power is shifting to workers. This is new. We have lived through 40 years of labour surpluses. Employers have been calling the shots, and increased credentialism was a way to filter through high numbers of applicants for every job opening. But already in British Columbia and Quebec, the number of job openings barely exceeds the number of unemployed people. This is coming to a neighbourhood near you. More businesses will hire people without paper credentials, and they will be willing to train on the job.

Where do skills come from?

Both the volume and location of skills development is shifting for residents of Canada, from certification in universities and colleges (costly in both dollars and time), to shorter-term, more targeted skills certification in a variety of public and private settings and more on-the-job training than has occurred in decades. Expect to see an increase in inequality. Over the last 30 years, as more people completed degrees and certificates, the market of people with such credentials ballooned and the wage premium for post-secondary education fell. The value of these credentials was more to help you get a permanent full-time job than to earn better pay. Now those who can afford the time and money to get a degree, particularly from Ivy League institutions, are likely to see a return of the wage premium. This will increase income inequality.

More on-the-job training is likely, but this raises the free-rider problem: a business may invest in recruiting and training workers, but how do they prevent the loss of returns on this investment if that worker moves over to a competitor who pays more, but didn’t incur the costs of training in the first place? The degree to which public institutions offer relevant short-term and low-cost skills development options will maximize human potential or constrain it, making us turn more to immigration as a solution in the event of sub-optimal skills development options for Canadians.

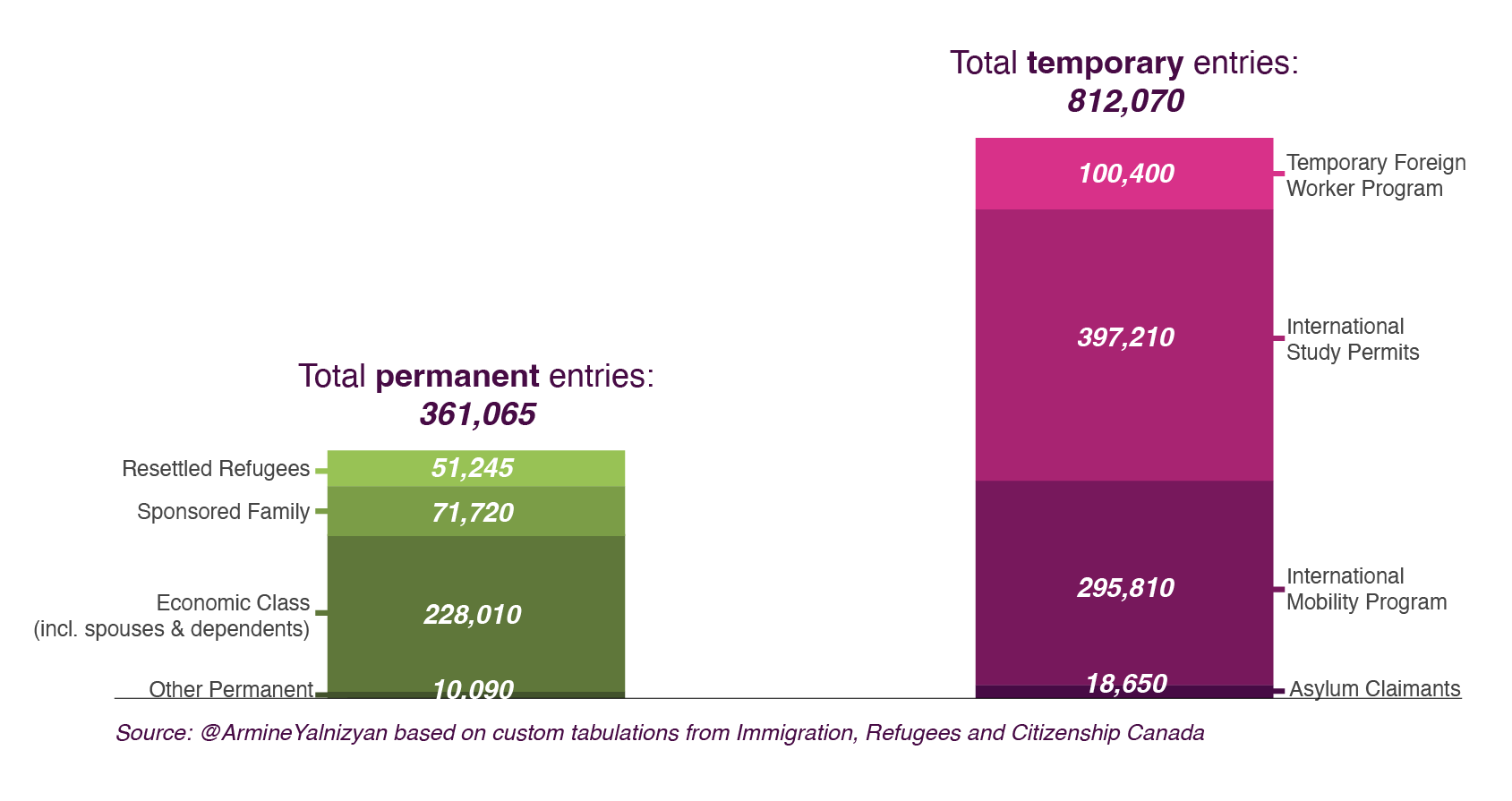

Although the discussion among policy experts, academics and decision-makers refers to the relationship between immigration and skills development, since 2006 immigration has been eclipsed by the use of temporary foreign workers who enter Canada through a variety of programs on temporary resident visas. This trend has continued to accelerate, even in the pandemic. By November 2021, 1.2 million newcomers entered Canada. Less than a third were permitted to remain. Addressing labour shortages by making more people “permanently temporary” augurs poorly for the future of this “nation of immigrants”.

From January to November 2021, Canada admitted 1,173,135 newcomers. Only 31% were permitted to stay permanently.

Will robots eat all of the jobs?

What technology always does is unbundle tasks from jobs. Automation and container shipping led to the outsourcing of blue-collar jobs to cheaper wage jurisdictions. Now digital technologies can relocate aspects of work usually done by white collar workers and professionals like lawyers, architects/drafters, engineers, medical diagnosticians, software developers, and others whose high skills normally command high pay. What happens when a cheaper “you” is available on a just-in-time basis from another part of the world? The typical policy response for displaced workers is “more training”. But how and for which jobs do you reskill the group that is already the most skilled? And what are the ramifications for a world struggling to create inclusive growth for everyone, as we add new voices to the chorus of those who feel aggrieved and left behind?

Many nations are struggling with these same three megatrends. They present both the threat of a race to the bottom, and the knowledge that some nations will be more successful than others, offering an example to emulate. Why shouldn’t Canada take the lead in a race to the top?

Armine Yalnizyan is an economist and the Atkinson Fellow on the Future of Workers. She spoke at the Future Skills Summit recently as part of a leadership panel discussion on “the next steps for a future-ready workforce.” You can follow her on Twitter @ArmineYalnizyan.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint, official policy or position of the Future Skills Centre or any of its staff members or consortium partners.