Skills Training for Youth

With employers reporting skills gaps in their workforce, the need for structured training and upskilling programs that equip youth for employment success has never been greater.

The employment and skills training landscape has experienced dramatic changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the fields of digitization, automation, innovation and education. The additional challenges of facilitating and investing in technological infrastructure (high-speed internet), virtual skills training and education, access to digital equipment and basic digital literacy has disrupted skills training within the labour force. Moreover, skills training organizations ranging from community groups to academia are not meeting the needs of learners or equipping job seekers with the tools they need.

According to 2022 estimates, there are about 7.3 million youth aged 15 to 29 years living in Canada. The youth population is not homogeneous. Youth aged 18 to 24 years have been hit particularly hard during the pandemic, especially with respect to employment, skills training and education. Experiences include a high rate of job loss and unemployment, stopping or changing education plans, a drop in earnings and a general impact on day-to-day existence. Additionally, youth from equity-seeking groups are more likely to encounter discrimination in hiring practices, which is made worse by an unstable labour market. Research from the Diversity Institute shows that youth from equity-seeking groups experienced significant challenges to skills training before the pandemic, which worsened due to massive job loss and the closure of academic and training institutions. Ensuring youth do not fall further behind in their skills development is of paramount importance.

In this blog post, we examine the experience of skills training among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the perceived needs of youth aged 18 to 24 years. Using survey data collected between March and April 2022 by the Environics Institute in partnership with the Diversity Institute and the Future Skills Centre, we uncover a somewhat haphazard approach among youth and their employers with respect to skill development. We offer suggestions on what can be done in the skills ecosystem to encourage a more focused approach to skills training. Among survey respondents, 10% of youth self-identified as Indigenous, 14% as South Asian, 7% as Chinese, 6% as Black, 16% as belonging to another racialized group and 25% as immigrants. This diversity reflects that of youth across Canada.

Consistent with work by ESDC on “Skills for Success,” youth recognize that communication and adaptability are among the top skills they need to succeed in the workforce. But, previous research has suggested that the ways in which they conceive of these skills may differ from the definitions by employers.

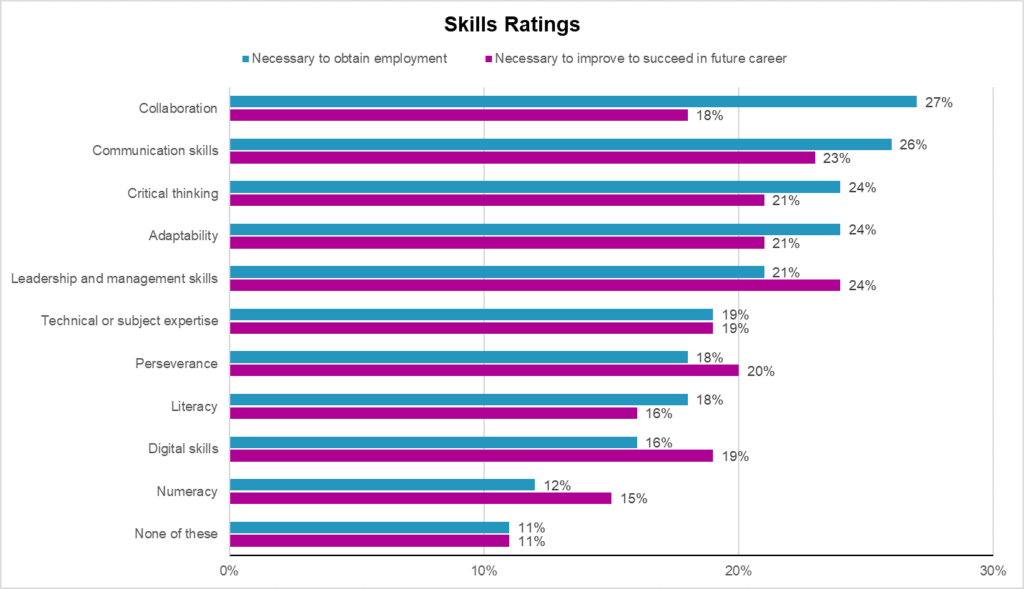

Nevertheless, young workers are aware of their need to develop communications skills and other skills for success. Survey results indicate that when asked about which skills are important to get one’s main job, youth rated the following four as important: critical thinking, or the ability to solve problems; communication; the ability to collaborate or work in teams; and adaptability (Figure 1). When asked which skills would be needed to be successful in one’s career, they listed many of the same skills, plus leadership and management. Interestingly, collaboration is ranked as the top skill for obtaining employment, but is considered less important for job success.

Figure 1. Foundational skills highlighted by youth as important for gaining employment and being successful in one’s career (n=774).

A Haphazard Approach to Skills Training?

The pandemic was a disruptive time for many workers. Given the even greater setbacks faced by youth, however, it is especially imperative to provide them with training resources to ensure they do not suffer long-term labour market consequences. Since the start of the pandemic, only one-half (51%) of youth participated in work-related training programs provided by their employer and 26% participated in work-related training not provided by their employer. Only 28% of youth participated in a work-related training course because they became unemployed or were working fewer hours owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.

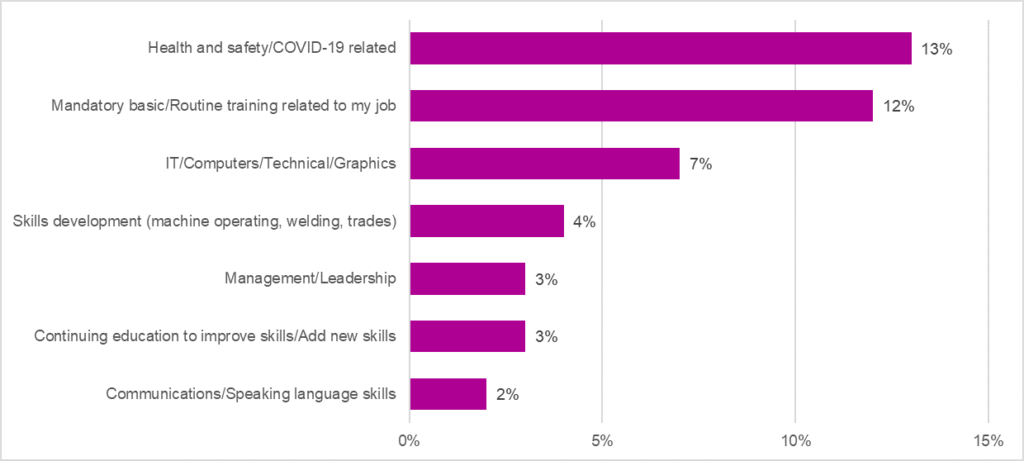

Among the 26% of youth who provided details on the type of training they completed (Figure 2), the areas in which they received training were not focused on any particular area. More strikingly, the areas in which they completed training did not match the skills they said they needed for career success. Research shows that the Skills for Success model is built on a framework that is responsive to the changing needs of the job market. However, only 3% of youth completed training in management or leadership training, and 2% took training to improve their communications. It would appear that the approach to work-related training is haphazard at best. The reasons for this warrant further exploration with an equity, diversity and inclusion lens and consideration of the employer’s role in supporting relevant training opportunities for youth.

Figure 2. Type of training received by youth aged 18 to 24 years (n=326).

The Role of the Skills Ecosystem

While understanding the skills profile of youth is important, it is equally valuable to understand what is lacking in the skills development landscape. From the survey results, it is clear that youth value essential skills identified in the Skills for Success Model, which include adaptability, collaboration, communication, creativity and innovation, digital literacy, numeracy, problem solving, reading and writing. However, the Diversity Institute’s pan-Canadian sample of organizations serving youth younger than 29 years old indicated that only 55% of these organizations provide skills training connected to foundational skills.

Additional research found that 54% of employers indicated that youth were not even “moderately prepared to meet the needs of the emerging job market.” To ensure youth can access resources to help build these skills for success, it is crucial training programs for youth include these skills for success. Additionally, employers can re-evaluate and restructure their hiring practices and skills assessments to ensure they are free from bias and inclusive, particularly for young jobseekers from equity-seeking groups. Offering wraparound supports to enhance accessibility of these programs may also encourage greater uptake. To this end, upcoming Diversity Institute research on wraparound supports and programs for equity-seeking groups will examine what services are needed to ensure any potential skills gaps can be met.

The Path Forward

With many employers reporting skills gaps in their workforce, it is vital for industry leaders (government, business, academia and skills organizations) to reconsider their approach to engaging youth. At the same time, Canada is experiencing a shift from traditional training systems with credentials to ones that focus on skills development and work-integrated learning. This shift signals that skills and abilities can no longer be exclusively diploma-oriented, as this may not fulfil labour demands.

Training, skills development and upskilling efforts need to keep pace with these shifts and the needs of youth jobseekers. For example, micro-credentials are garnering attention and importance in workforce development due to their nature of stacking ability, flexibility and integration with other credentials. It is critical to identify in-demand skills and create innovative and sustainable working environments for youth. By targeting the skills needed across sectors, training providers can better equip youth for employment success.

Diversity Institute research highlights best practices that can help to close the gaps for youth in the workforce, particularly racialized youth. Strategies include informed decision-making, leveraging mentors and role models with programs like ELITE Program for Black Youth, bridging the digital divide, developing partnerships through programs like FirstWork to deliver programs and services, and evaluating and building youth-focused programs through organizations like YouthREX. Jelly Academy digital marketing courses provide reskilling and upskilling, industry partnerships and funding opportunities for eligible students. Additionally, work-integrated learning models provide frameworks for experiential learning, and programs like ADaPT (Advanced Digital and Professional Training); Study Buddy, an interactive online tutoring program; NPower Canada no-cost information technology training programs, and Mitacs paid internships provide in-demand skills training for youth, and focus on serving youth from equity-deserving groups.

By planning structured training and upskilling programs across all sectors, we can build a solid and sustainable labour market for youth.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint, official policy or position of the Future Skills Centre or any of its staff members or consortium partners.