The Advanced Digital and Professional Training Program (ADaPT): Inclusive Digital Upskilling

Demand for digital skills has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic; it extends beyond the information and communications technology (ICT) sector to virtually every industry. The development of artificial intelligence (AI), augmented reality and virtual reality, the Internet of Things, cybersecurity and robotics make possible what was once only imagined in science fiction. Few are able to keep pace with the potential: The sudden emergence, for example, of ChatGPT threatens to disrupt everything from journalism to post-secondary education.

For the last 20 years, industry has trumpeted the need for more digital skills. While large technology employers tend to dominate the discussion, the demand is most acute among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which account for 90% of private sector employment, as well as in government and non-profits. Recent labour market research shows that there are more ICT jobs outside of the ICT sector as other sectors, such as retail, finance, manufacturing and services, accelerate their rates of digitization.1 The digital skills gap is also imperiling innovation and economic growth.2

Canadian companies lag in their adoption of new technologies; despite the potential of leading-edge inventions, products and services, without adoption, there is no innovation. Innovation is not only about making new technologies, but also about using them to “do” differently. Canada needs to step up its game if it is going to reap the promise of new technologies and digitization, regardless of sector. For example, one study by Statistics Canada revealed that only 10% of large firms had adopted AI; this dropped to 3% for SMEs.3 We also need a more nuanced understanding of the skills in demand.

While the appetite for programmers and engineers is unabated, a recent survey by the Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC)4 indicated the top three “technology” roles were project managers, business analysts and business development management roles. Given the pace of change, many of the emerging roles most in demand are not even included in the occupational nomenclatures for the sector.

Yet, while employers claim that there are profound skills shortages, there is also evidence that they are underusing certain talent pools, including women; Indigenous Peoples; racialized people, particularly those who are Black; persons with disabilities and internationally trained professionals. For example more than 40% of internationally educated engineers are under-employed. 5 Among ICT workers, there is a severe under-representation of Black Canadians and Indigenous Peoples;6 only 1.2% are Indigenous.7 In addition to systemic barriers, workplaces can be hostile or even toxic, which underscores the need to rethink the definition of digital careers, to ensure we are capitalizing on the overlooked wealth of talent from equity-deserving groups.

The Advanced Digital and Professional Training program

The Advanced Digital and Professional Training (ADaPT) is an employer-centered, work-integrated learning program created in 2013 by the Diversity Institute (DI) with support from the Future Skills Centre to address the skills gap between post-secondary school graduates and the entry-level job market. It aims to expand the talent pool and advance inclusion by providing alternative pathways into ICT and digital roles for graduates of varied academic backgrounds.

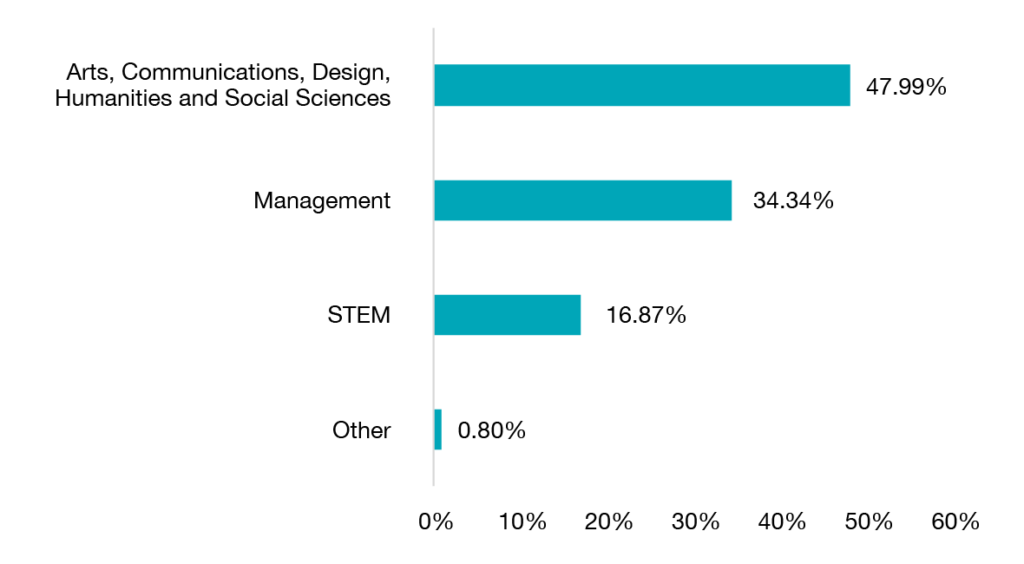

Since the first cohort began in 2014, the program has been provided to more than 1,200 youth and led to more than 1,000 work placements. About 48% of participants come from arts and social sciences backgrounds. The model has also been used to help transition newcomers with international credentials into well-paid work.

Courses provide training for in-demand technology skills, such as coding and data analysis; and skills for success, such as business writing and presentations. The program also offers wraparound supports, including career counselling and coaching, coupled with work-integrated learning and supports to address the needs of women and diverse learners.

The results speak for themselves. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the program shifted to virtual delivery, ADaPT placement rates exceeded 90%. Moreover, 79% of participants identify as belonging to one or more equity-deserving groups, demonstrating success in providing opportunities for students from diverse backgrounds.

The ADaPT program was developed with support from the Government of Ontario, the Government of Canada and HSBC Canada in collaboration with TECHNATION Canada. Also supporting its development are the Ontario Chamber of Commerce; the Ontario Tourism Education Corporation; large employers such as the Royal Bank of Canada, TCS Canada, Cognizant Technology Solutions Canada Inc., Infosys Ltd., Tech Mahindra Ltd. and Public Safety Canada; and organizations offering specialized training, including Pegasystems Inc., General Assembly Online, Salesforce Inc. and Jelly Academy.

Responding to employer needs

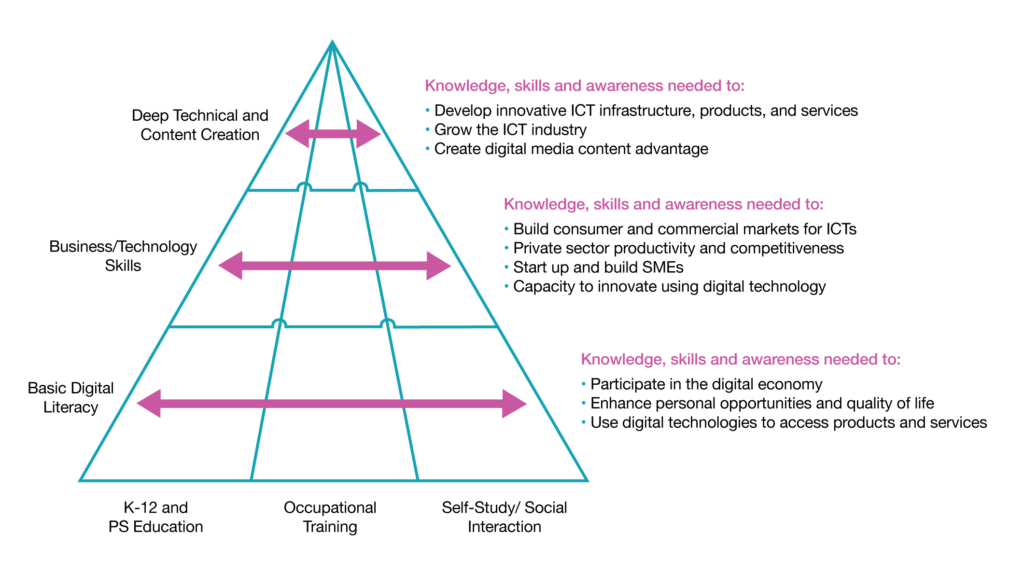

While there is a tendency to equate digital skills with computer science and engineering,8,9,10 and these are in high demand, there is a much broader range of skills needed to advance the adoption and effective use of new technology. When employers say they need digital skills, they often are not referring to deep technology skills like programming and systems design, but instead to the skills to use technology and basic computer applications. An OECD study showed that while “digital skills” were most cited in a survey of Ontario employers, only 10% referred to “deep” technology skills (normally acquired through years of study). Another 15% were referring to skills like technical support or applications like SQL. Fully 75% were referring to simple Microsoft Office applications, like Excel; the latter remains one of the top technical skills employers need.11

This is not to say that we should not continue to double down on encouraging more women, Indigenous Peoples and other equity-deserving groups to study computer science and learn coding. But it is critical to understand that the skills needed to advance technology adoption and innovation include an understanding of organizational processes, user needs and regulatory policies. Some roles require “hybrid” or multi-skilled individuals with expertise in sales, marketing, project management, regulatory processes, business management, strategy and organizational change, and content development.12,13 Thus, it is important to distinguish between different levels of digital skills and their applications (Figure 1).

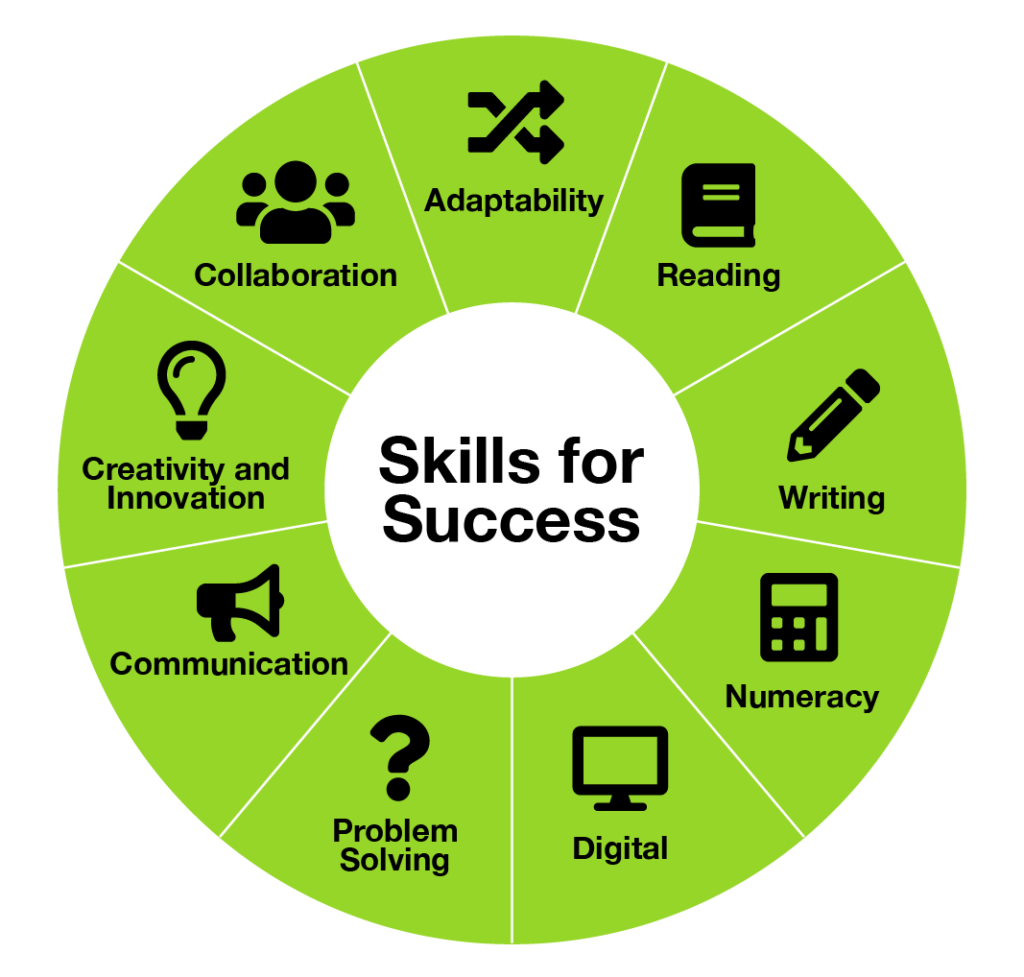

Studies have also highlighted the importance of other skills for employment,14 and a recent report from the ICTC indicates that while demand for technical skills remains high, employers are looking for employees with communication and interpersonal skills, the ability to work in teams and strong business acumen.15 This confirms other Future Skills Centre research on the importance of social and emotional intelligence and aligns with the Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) Skills for Success framework.16 This framework has identified nine essential skills that will help individuals to find employment and succeed in their careers (Figure 2). These are supported by other frameworks; for example, from the World Economic Forum, which increasingly emphasize adaptability, creativity, innovation and collaboration.17

Program design

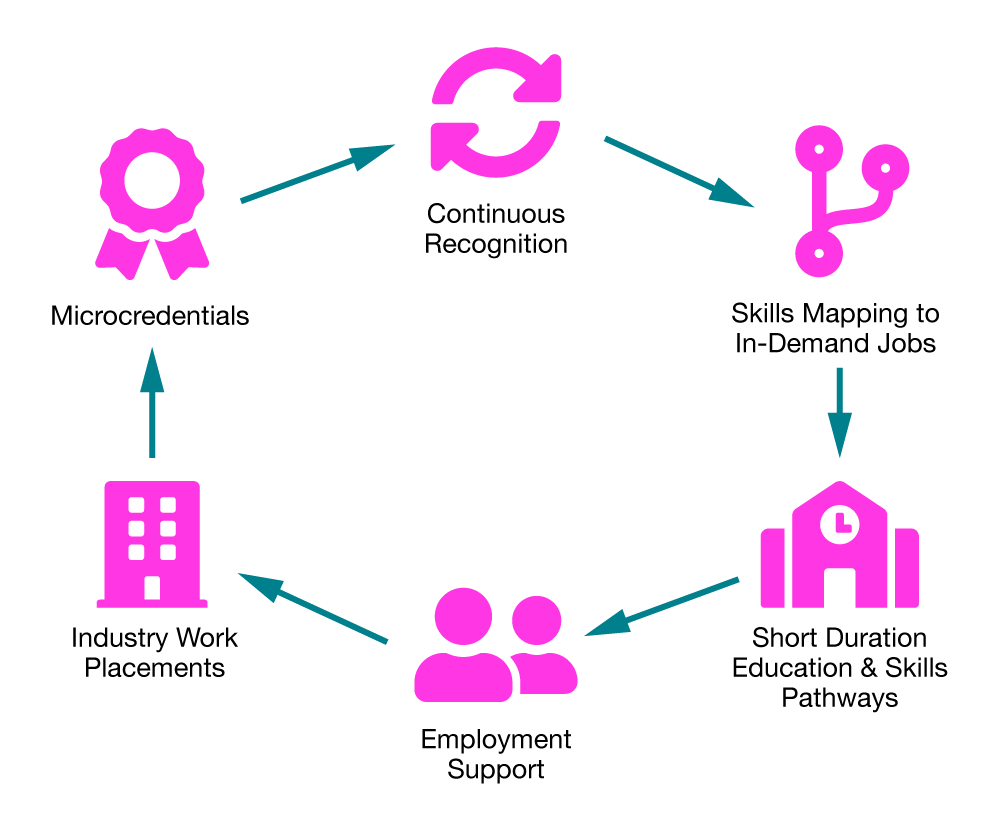

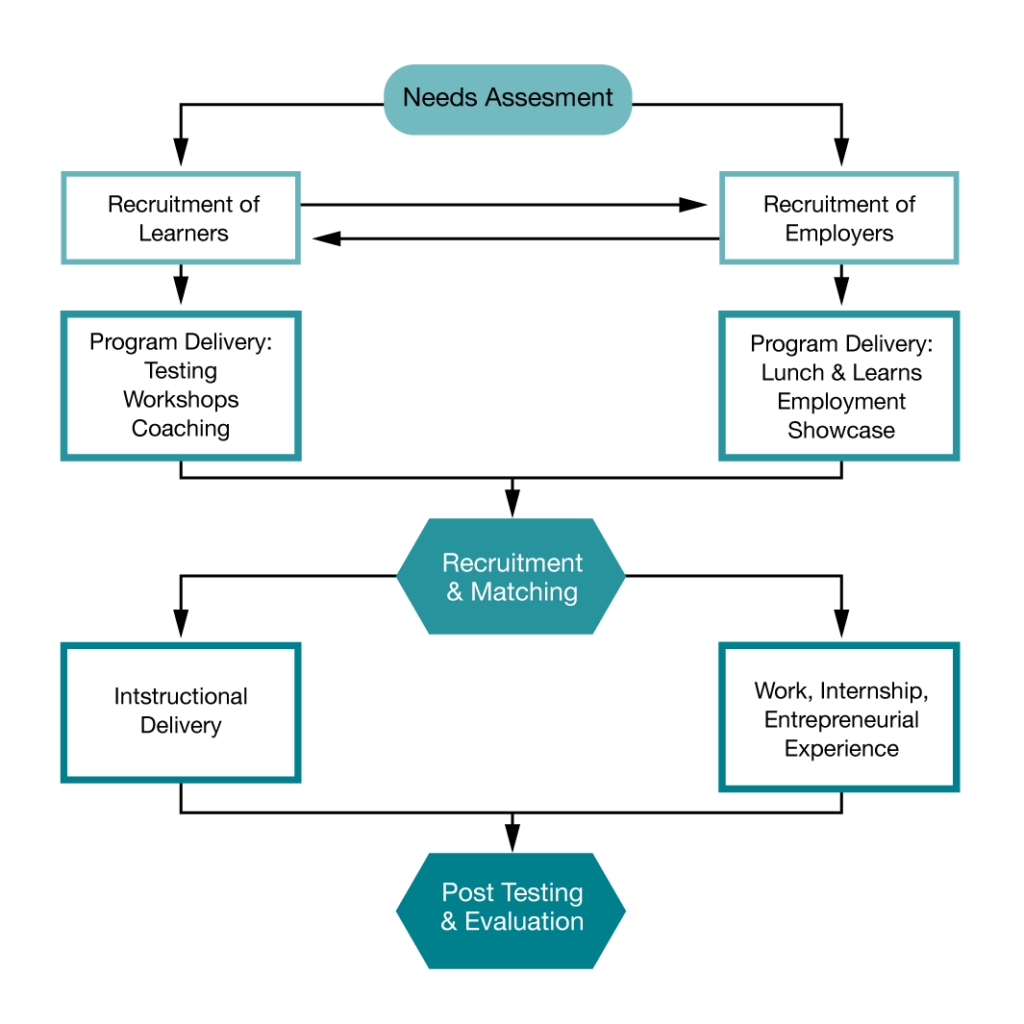

Clearly defined competency frameworks with measurable learning outcomes are critical, but so are wraparound supports tailored to the needs of learners. Central to program design is the recognition that employers need to rethink some of their assumptions about credentials and the talent they need. Taken together, these elements make ADaPT unique and effective. The unique rapid response upskilling model developed and implemented through ADaPT allows it to respond to emerging needs (Figure 3).

The ADaPT logic model (Figure 4) addresses supply (learner needs) and demand (employer needs) and recognizes that bridging the skills gap requires attention to both. For learners, elements include:

- Clearly defined learning outcomes

- Recruitment of targeted diverse learners

- Rigorous screening

- Competency frameworks to inform curriculum design

- Pedagogy tailored to diverse students

- Wraparound supports.

On the employer side, elements include:

- Widespread recruitment and engagement

- Consultation on talent needs

- Training to advance more inclusive practices from job design to recruitment and advancement strategies.

At each stage data is collected, analyzed and fed back to inform program design using tools that include up-front skills assessment and psychographic assessments, pre- and post-testing and evaluation, and hands-on skills development combined with self-study and online learning.

The core ADaPT program was designed for senior post-secondary students and graduates but has evolved to meet the needs of other groups, for example, newcomers and, more recently, senior high-school students.

Selection includes a range of techniques, including interviews and testing, with employers sometimes involved. Scores are assigned based on an applicant’s grade point average, written and oral communication skills, resume, coachability and interpersonal skills. Equity-deserving groups are prioritized. Standardized tests are used to assess basic skills and the big five personality traits: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. Employability is another critical screening factor and is evaluated on the basis of previous professional work, or volunteer and extracurricular experience.

The core ADaPT curriculum consists of workshops on in-demand digital skills and competencies and professional skills and competencies. The workshops have evolved and are validated periodically by employers. Core digital workshops include Intro to HTML Coding, Quantitative Methods using Excel, Data Analytics using Excel, UX Design Fundamentals, Adobe Illustrator and InDesign, and Search Engine Optimization and Google Analytics. Professional workshops include Business Writing, Career Development Strategies (e.g., resumes, LinkedIn profiles), Networking and Personal Branding, Communication Styles, Presentation Skills, Sales Fundamentals and Design Thinking. This core curriculum is designed to produce strong, entry-level workers with a robust mix of the skills most employers require in the digital marketplace quickly.

ADaPT also provides wraparound supports that enable the engagement of a wider range of participants. These include career coaching to help participants solidify their job search skills and work placement, in which ADaPT works with employers to match participants to the employers’ entry-level hiring needs. In addition, participants are connected to potential job openings and encouraged to compete for placements.

The program also works with employers to meet their skills needs and to enhance participants’ employment success. This includes speaking with employers to identify the skills gaps they are facing, working closely with them on potential job postings and needs, and giving them access to supports to help them advance their equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) practices. For example, employers get access to DI’s Diversity Assessment Tool, a range of training and advisory services, and specialized tools such as the Micropedia of Microaggressions and the hireimmigrants.ca and discoverability.ca resources. Recently, through the Future Skills Centre, DI has partnered in the development of a learning management system to support SMEs across Canada. And as an ecosystem partner in the Government of Canada’s 50 – 30 Challenge, DI is providing resources to support organizations on their EDI journey, including online tools.

Evaluation and impact of the ADaPT program

The program has been formally evaluated to assess the learner experience, the employer experience and its impact. Surveys are distributed to participants at three stages: Stage 1 (pre-training), Stage 2 (post-training) and Stage 3, four months post-training (during internships). Participants score their perceptions of skill proficiencies in different areas, including essential skills, interpersonal skills, thinking skills, technical skills and other areas. Standardized tests are used to assess competencies and skills development (e.g., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Education and Skills Online test and Lumina Spark). Third-party evaluations, including a recent one from Blueprint, have confirmed ADaPT’s efficacy, and with the Future Skills Centre, Blueprint ADE is overseeing a randomized controlled trial to compare components of the program and assess their impact.

Serving graduates from more than 100 universities, ADaPT has trained more than 1,200 youth, 79% of whom identify as being diverse. The program averaged placement rates of over 90% and satisfaction rates of 88% even during the shift to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

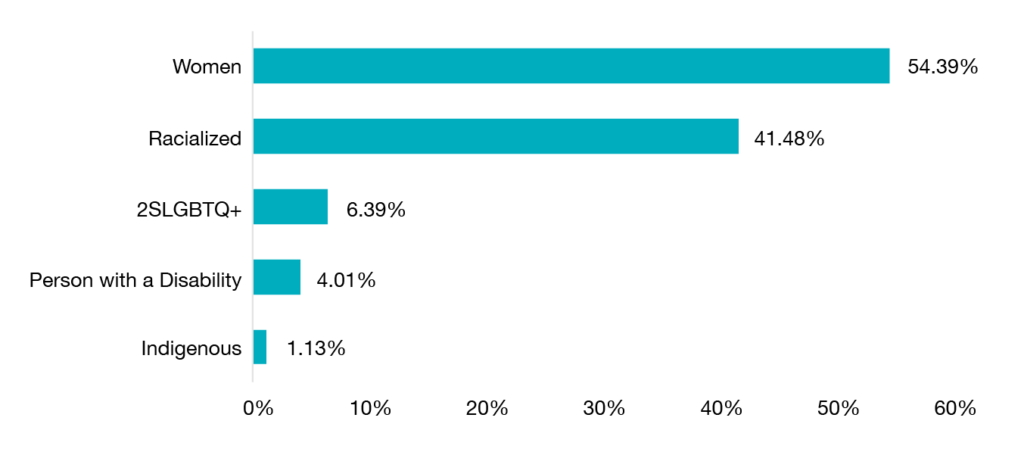

The program successfully recruits diverse participants.18 Of the 798 individuals that responded to the demographic questions, 54% self-identified as women, 41% as racialized, 6% as 2SLGTBQ+ and 4% as persons with a disability (Figure 5). About 1% of ADaPT participants identified as Indigenous. Participants also come from various fields (Figure 6).

|

Demographics |

(%) |

|---|---|

| Indigenous | 1.13% |

| Person with a disability | 4.01% |

| LGBTQ2S+ | 6.39% |

| Racialized | 41.48% |

| Women | 54.39% |

|

Field of study |

Core |

|---|---|

| Other | 0.8% |

| Science, technology, engineering and math | 16.87% |

| Management | 34.34% |

| Arts, communications, design, humanities and social sciences | 47.99% |

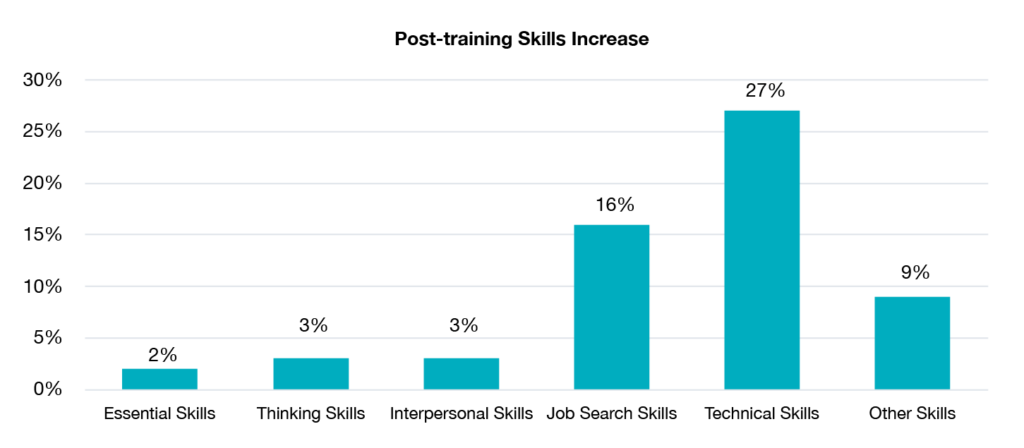

ADaPT participants reported increased proficiency after receiving training for every skill measured, with the largest increases for technical and job search skills (Figure 7).

| Post-training Skills Increase | % |

|---|---|

| Essential skills | 2% |

| Thinking skills | 3% |

| Interpersonal skills | 3% |

| Job search skills | 16% |

| Technical skills | 27% |

| Other skills | 9% |

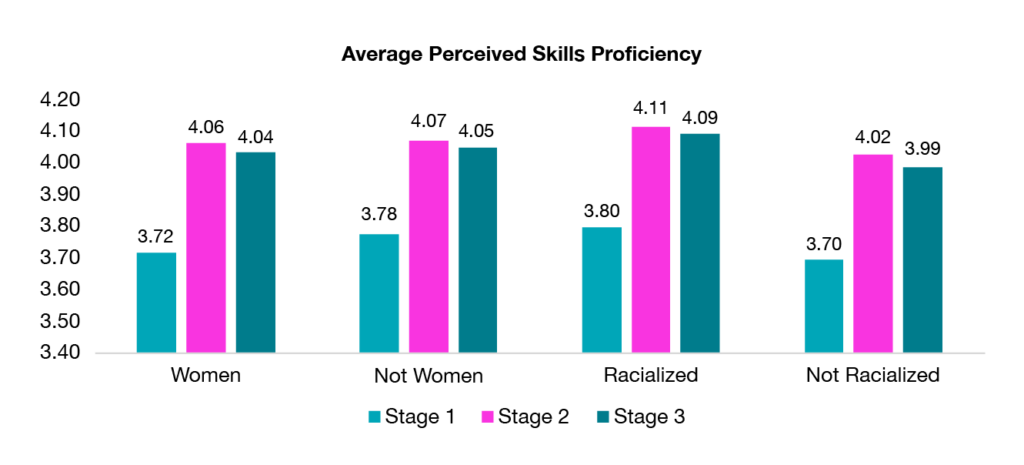

The ADaPT program also benefitted women and racialized people, with each group reporting improved perceptions of skills proficiencies (Figure 9). Analysis also showed a decrease in women’s and racialized participants’ perceived need for assistance with skills, which means they gained confidence during the training.

Of interest is that women started with slightly lower scores for perception of skills (3.72 vs. 3.78), but ended at almost the same score as men (4.04 vs. 4.05). Racialized participants started and ended at a higher level of perceived proficiency than non-racialized participants.

| Women | Not women | Racialized | Not racialized | |

| Stage 1 | 3.72 | 3.78 | 3.80 | 3.70 |

| Stage 2 | 4.06 | 4.07 | 4.11 | 4.03 |

| Stage 3 | 4.04 | 4.05 | 4.09 | 3.99 |

Conclusion and looking ahead

The ADaPT program is bridging the skills gap between post-secondary graduates and employers. It is an action-research project demonstrating a successful hybrid model for skills development with an aim of expanding the talent pool and advancing inclusion. It does this by providing alternative pathways into ICT and digital roles for graduates from various academic backgrounds. To cater to a wider audience, the program has been offered in face to face, online and blended formats to create a scalable delivery approach and to accommodate diverse ways of learning.

The program continues to be responsive and to identify opportunities for improvement. It pivoted when the COVID-19 pandemic began; the online stream opened up ADaPT to people it could not have otherwise reached. The synchronous and asynchronous delivery stream offers the potential to reach more groups. The program has been adapted, for example, to meet the needs of mid-career professionals, particularly newcomers; and youth, including high-school students from equity-deserving groups.

For example, in 2022–2023 ADaPT courses in foundational digital skills are being offered to Grade 11 and 12 Peel District School Board students, with a focus on Black and Indigenous students, and to Black youth aged 15 to 29 years in Ontario as part of the Black Youth Action Plan program. With the support of the Future Skills Centre and ESDC Skills for Success, as well as the Canada Digital Adoption Program, and with partners like the Ontario Chamber of Commerce, ADaPT has been adapted to provide upskilling to a broader range of learners, with a particular focus on meeting the needs of SMEs. Components of ADaPT are also being used in leadership development programs for women and other equity-deserving groups through the 50 – 30 Challenge. The curriculum is continuously updated with new in-demand microcredentials, as well as certifications from Salesforce, Pega, Google, Microsoft and others.

Authors at the Diversity Institute:

Wendy Cukier, co-founder and academic director

Brian Robson, director, business development and training programs

Saifur Rahman, research assistant

Amira Higazy, research assistant

Rim Abid, postdoctoral research fellow

Guang Ying Mo, director of research

1 Herron, C., & Ivus, M. (2021). Digital economy annual review 2020. Information and Communications Technology Council. https://www.ictc-ctic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ICTC-Annual-Review-2020-EN.pdf

2 Shortt, D., Robson, B., Sabat, M. (2020). Bridging the digital skills gap: Alternative pathways. Public Policy Forum. Diversity Institute. Future Skills Centre.

3 Statistics Canada. (2019). Survey of innovation and business strategy. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190313/dq190313b-eng.htm

4 Ivus, M., Kotak, A. (August 2021). Onwards and upwards – Digital talent outlook 2025. Information and Communications Technology Council. https://www.ictc-ctic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/digital-talent-outlook-for-2025.pdf

5 Ontario Society of Professional Engineers. (2015). Crisis in Ontario’s engineering labour market: Underemployment among Ontario’s engineering-degree holders. https://www.ospe.on.ca/public/documents/advocacy/2015-crisis-in-engineering-labour-market.pdf

6 Vu, V., Lamb, C., Zafar, A., (2019). Who are Canada’s Tech Workers. Brookfield Institute. https://brookfieldinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-Tech-Workers-ONLINE.pdf

7 Cameron A., Cutean, A. (2017). Digital economy talent supply: Indigenous peoples of Canada. Information and Communications Technology Council. https://www.ictc-ctic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Indigenous_Supply_ICTC_FINAL_ENG.pdf

8 Cukier, W., Shortt, D., & Devine, I. (2002). Defining information technology: The gender implications. In W. Auer-Rizzi, C. Innreiter-Moser, & E. Szabo (Eds.), Management in a global, yet diverse world: Perspectives across Europe and North America. Johannes Kepler University.

9 Cukier, W., Smarz, S., Baillargeon, A., Rylett, T., Munawar, M., Hsu, C., Hannan, C., & Yap, M. (2010). Improving Canada’s digital advantage: Building the digital talent pool and skills for tomorrow. Diversity Institute. PDF filehttps://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/diversity/reports/full_digital-economy_report_and_bibliography_dec15.pdf

10 Williams, J. C. (2015). The 5 biases pushing women out of STEM. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/03/the-5-biases-pushing-women-out-of-stem, external link

11 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2020). Preparing for the future of work in Canada. https://doi.org/10.1787/05c1b185-en

12 Shortt, D., Robson, B., & Sabat, M. (2020). Bridging the digital skills gap: Alternative pathways. Skills Next Series. Public Policy Forum, Diversity Institute and Future Skills Centre. https://ppforum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/DigitalSkills-AlternativePathways-PPF-JAN2020-EN-1.pdf

13 Cukier, Wendy, Smarz, S., and Grant, K. (2017). Digital skills and business school curriculum. Ryerson University.

14 Shortt, D., Robson, B., & Sabat, M. (2020). Bridging the digital skills gap: Alternative pathways. Public Policy Forum. The Diversity Institute. Future Skills Centre. https://ppforum.ca/publications/bridging-the-digital-skills-gap/, external link

15 Herron, C., & Ivus, M. (2021). Digital economy annual review 2020. Information and Communications Technology Council. PDF filehttps://www.ictc-ctic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ICTC-Annual-Review-2020-EN.pdf, external link

16 Cukier, W., McCallum, K.E., Egbunonu, P., Bates, K. (2021). The mother of invention: Skills for innovation in the post-pandemic world. Public Policy Forum, Diversity Institute, Future Skills Centre. https://www.torontomu.ca/diversity/reports/the-mother-of-invention/

17 World Economic Forum. (2015). Collaborative innovation transforming business, driving growth. PDF filehttps://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Collaborative_Innovation_report_2015.pdf, external link

18 Blueprint. (2022). Advanced digital and professional training (ADaPT) Evaluation. https://www.blueprint-ade.ca/insights/evaluating-future-skills-solutions

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint, official policy or position of the Future Skills Centre or any of its staff members or consortium partners.