Workforce Shortages Drag on Productivity: Bridging the Divide in Healthcare, Trades, and Tech

Canada is short 64,000 skilled workers including engineers, tradespeople, nurses, and educators. This shortage cost the economy an estimated $2.6 billion in lost GDP in 2024, significantly dragging down Canada’s productivity growth.

Productivity measures how much we produce with the resources we have. It’s a core driver of living standards. When productivity growth slows down, the economy generates less new income––leaving less to share between Canadian workers, businesses, and governments.

Our recent research delves into these labour shortages, offering actionable solutions to bridge skills gaps and enhance Canada’s productivity, ensuring a more resilient and competitive workforce.

Labour shortages: A persistent challenge

Overall conditions in the labour market are normalizing, with unemployment and vacancy rates returning to pre-pandemic levels. While the widespread shortages seen during the pandemic have eased, the variation in vacancy rates across occupations has widened considerably. So even as conditions stabilize, many roles still face persistent shortages.

The workers we need are higher skilled than the average employee

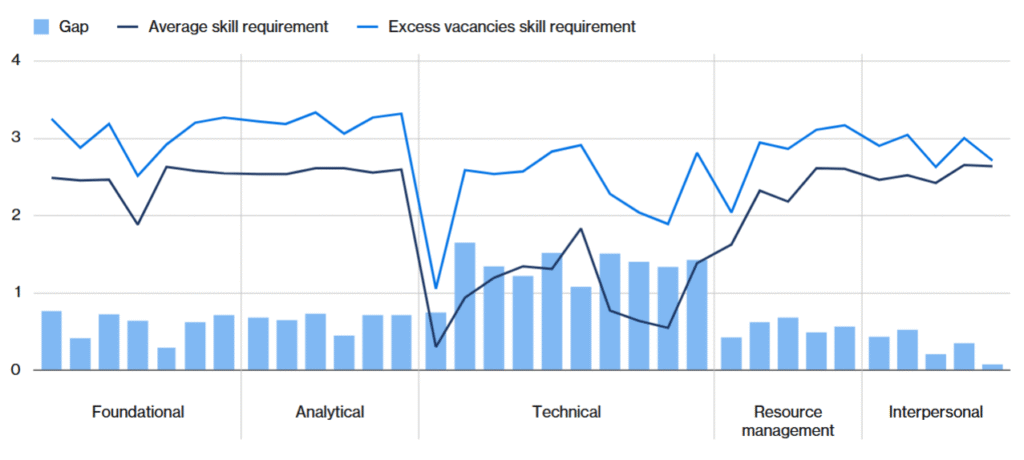

We clustered occupations with similar skill profiles to capture the broader impacts of skills shortages rather than analyzing occupations in isolation. By comparing current vacancy rates to pre-pandemic levels, four occupation clusters stand out as being in the greatest shortage of skilled workers: engineers, technical occupations (primarily in healthcare), higher-skill goods (skilled trades), and higher-skill services (especially nurses and educators). These occupations require workers with above-average proficiency across all skill categories—with the largest gaps in technical skills. (See chart below.)

Occupations with excess vacancies have higher skill proficiency requirements than the average role in Canada

(OaSIS skill proficiency ratings for roles with excess vacancies and all roles, 2024Q3)

Sources: Statistics Canada; The Conference Board of Canada; Employment and Social Development Canada

Addressing these skills shortages will not be an easy fix. It will require substantial retraining of the current workforce and attracting new workers with the technical skills needed.

Traditional solutions are no longer enough

Traditionally, labour and skills shortages have been addressed through three main levers: training and reskilling, interprovincial migration, and immigration. While each contributes to easing gaps in the workforce, none are sufficient on their own, especially when shortages are widespread.

- Training takes time. Nearly 80 per cent of vacant positions require formal post-secondary education, yet only 57 per cent of working-age Canadians (aged 25 to 64) hold such credentials. The occupations with the most acute shortages—engineering, nursing, education, and skilled trades—require multi-year degrees, diplomas, or lengthy apprenticeships.

- Interprovincial migration can’t alleviate widespread shortages. These critical occupations are experiencing shortages in skilled workers across all regions in Canada. While interprovincial migration can help ease localized gaps in lower-skill occupations, these measures won’t significantly reduce excess vacancies given the widespread nature and skill requirements of the shortages.

- Immigration isn’t fully aligned with labour market needs. Too few newcomers hold college diplomas or trade certifications that are urgently needed in skilled trades and higher-skill services such as educators and nurses. Many immigrants also face barriers such as credential recognition and licensing, which delay or prevent workforce entry.

It’s time for coordinated action

Shortages in higher-skilled occupations are likely to persist throughout the decade. Education and immigration policymakers have a key role to play—both in expanding training capacity and aligning immigration pathways with real labour market needs. Without bold, coordinated action from the government and education and training providers, these shortages will continue to strain critical sectors and limit Canada’s productivity.

The time to act is now.

Recommendations for university and college leaders

- Expanding programs in critical fields such as nursing, allied health diagnostics, electrical and power transmission installation, and other skilled trades, by increasing enrollment and graduation capacity.

- Strengthening student support through expanded access to financial aid, hands-on training placements, and career services to boost graduation rates and job readiness.

Recommendations for the federal government

- Adjusting Canada’s points-based immigration system to better prioritize skilled trades and technical occupations over university degree holders.

- Streamlining permanent residency for international graduates in high-demand fields like healthcare, education, and skilled trades.

- Expand the Foreign Credential Recognition Program to accelerate licensing and workforce integration for newcomers, especially in health and skilled trades.

By expanding training capacity, strengthening student support systems, and streamlining pathways for internationally trained professionals, Canada can build a more resilient and competitive workforce.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint, official policy or position of the Future Skills Centre or any of its staff members or consortium partners.